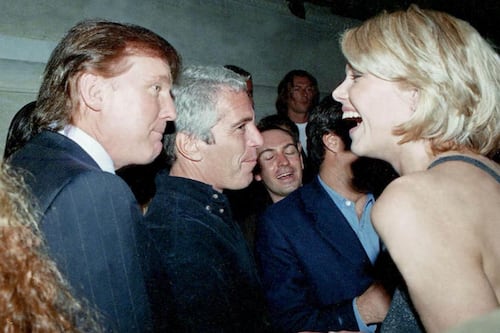

Trump afirma que Estados Unidos atacó objetivos del Estado Islámico en Nigeria tras atentados a cristianos

El Departamento de Defensa dijo que Estados Unidos trabajó con Nigeria para llevar a cabo los ataques, y que fueron aprobados por el gobierno de ese país.